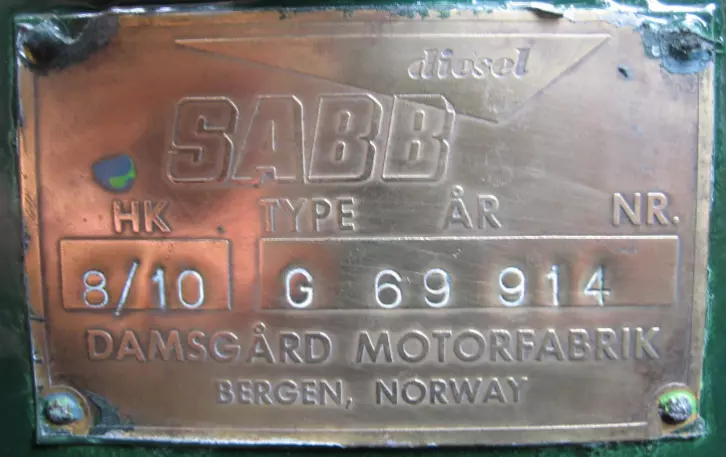

Following a series of semi-diesels, this was SABB’s first true diesel. Produced from 1955 to 2002, in total SABB manufactured some 24,500 of these little engines. Notably, the Type ‘G’ engines were splash lubricated. Splash lubrication is a system whereby “spades” on the big-end caps dip into the oil sump and splash the lubricant upwards towards the moving parts of the engine. Eliminating the need for an oil pump, this method adds to simplicity and reliability but only works on very low-revving engines. Otherwise the sump oil would be, literally, turned into a mousse resembling beaten eggs.

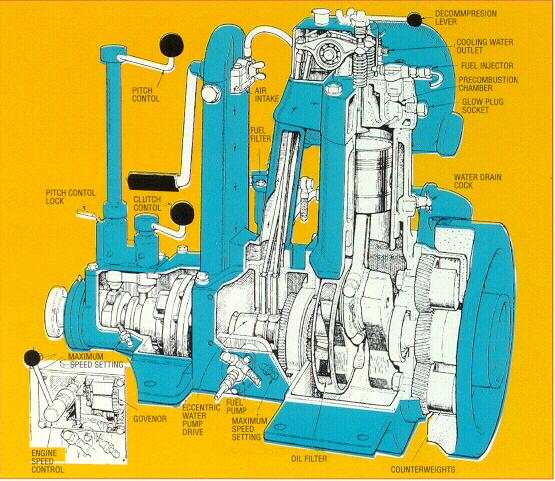

The Type ‘G’ had a huge roller big-end bearing running on a crank-pin and taper roller main bearings. Two lead-filled balance weights behind the flywheel helped reduce some of the primary out-of-balance forces. But make no mistake, this single cylinder engine made some noise and vibrated your boat. When the engine was warm, owners report being able to reduce the speed to just 60 RPM in neutral. That’s an explosion every two seconds on a four stroke engine!

The pinion gear on the crankshaft runs in a female gear with twice the number of teeth allowing the entire rear section to run at half the engine speed. In effect, it drives off the camshaft. A massive flywheel at front just fits on taper, with one large retaining nut. There is no automatic lubrication to top end apart from that provided by the owner’s oil can.

How does the clutch work on the SABB type G?

For engines that have a F-N-R setup as opposed to the variable pitch prop, there are actually two clutch drive plates. As you enable the forward gear with the lever, the entire propeller shaft and middle plate slides forward a little until the clutch engages. Once that happens and the prop is turning, the backward reaction force on the prop shaft keeps the clutch engaged. You can then remove pressure from the gear lever.

Reverse is the opposite, the entire shaft slides back a little until the reverse clutch engages. The prop turns and the reaction force acts to pull back, and the backwards force then holds it in all in gear.

When your boat is out of the water it is important to check that the prop can slide back and forth. If you ever have difficulty finding forward or reverse, you must check that you haven’t caught anything around the shaft. Common culprits are rope or barnacles. Before launching, always check that the shaft can move both directions and take care not to fit over-sized ring anodes or rope cutters that will prevent enough movement.

During operation, you need to push the gear lever home gently but firmly and hold it there for a second or so until the prop picks up speed and establishes a reaction force. Don’t run the engine in gear too gently at first or there will not be enough force from the prop to keep you locked in gear.

If your clutch starts slipping you’ll burn the plates and it’ll pop out into neutral. If you need to manoeuvre slowly, best practice is to use short bursts so you don’t pick up too much boat speed.

Old engines are worn out – right?

Some SABB type G’s are nearly seventy years old. So they must be worn out, right? The reality is that there’s very little to go wrong with these little engines. Many have been installed in ship’s lifeboats, and so will have seen very little use. But as many marine mechanics know, engines tend to die from neglect as opposed to from being overworked.