Stern Gear

Inboard engines require that the propeller shaft exits the boat beneath the waterline. This arrangement presents an obvious threat of water ingress. Traditionally, packing is used to create a tight seal around the shaft but the challenge is to keep the resistance to rotation at a minimum while keeping the water out. Modern dripless Lip Seal systems achieve this balance in another way and you can read about them over here. On this page though, let’s consider each element of the traditional system in turn.

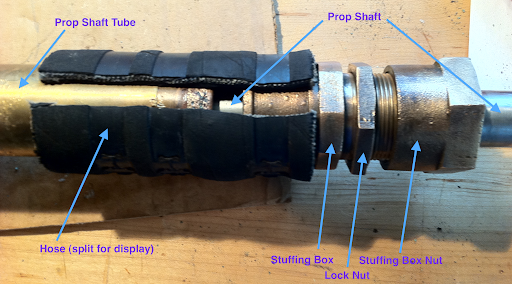

Depending on the underwater profile of your boat, you might only have a stern gland or you might have a stern gland and a P-bracket working together. The typical opening for the prop shaft is through a stern tube which is attached to the hull with a stern fitting of some type. The end of this tube is sealed to a stern gland via a flexible rubber hose. Remember that your engine is mounted on flexible mounts so some small movement must be expected. Forward of that (so towards the engine and gearbox) is a stuffing box which prevents the ingress of water into the bilges. This may or may not have a grease nipple and a greaser fitted. Note that the stern gear must not be tampered with when the boat is afloat.

Stuffing Box type stern gland

At its simplest, the basic ‘stuffing box’ or ‘packing gland’ has a few replaceable rings of ‘packing’ which encircle the shaft with in a tube. Packing is a square section rope traditionally made from flax, hemp or cotton. Modern versions can be found containing fibers manufactured from graphite and Kevlar. The packing prevents the ingress of seawater while providing a low-friction surface to allow the prop shaft to rotate. The tightening mechanism is a threaded ring that compresses the packing which, when wet, then ‘packs’ around the shaft creating a nearly water tight seal. A bit of water ingress is necessary to wet the packing’s fibres and cool the ‘bearing’.

If the packing is tightened too much, it can actually wear a groove in the prop shaft (thereby ruining it), so a balance must be reached between preventing water ingress and minimising frictional resistance to rotation. This balance point may require a slight drip of water during operation of the engine. One drip per minute is an established rule of thumb.

To Grease or Not To Grease?

Debate surrounds the topic of whether a stuffing box requires grease or not for optimum operation. Some argue that packing requires only sea-water to function properly and that grease can spoil the thermal conductivity of the system, and make quite a mess of your bilges at the same time. Others point out that a stuffing box with a positive supply of grease helps make the system effectively drip-less when idle. A squirt of fresh grease after a run will seal up the shaft until next time. If you do decide to go this way, there are several methods of supplying the grease;

- A greasing nipple for attaching a grease gun. A Grease Gun is an important piece of maintenance equipment on board and, if you have easy access to your stern gland, a few seconds labour will inject a dose of fresh grease.

- A Greaser Cup. These are small grease containers that attach directly to the stern gland. They are filled with a small amount of grease and a quarter-turn injects some into the stern gland.

- Permanently attached remote manual grease pump. This is perfect when access to the stern gland is limited or difficult. A large container is permanently attached via a hose to the grease point and, again, a quarter-turn when the engine stops will keep the gland water tight until next time.

A word of caution with all these methods is to be sparing with your use of grease. Too much will cause overheating of the gland packing material, leading to trouble.

Regarding which grease to use, many recommend Ramonol – “A high quality water resistant grease with good adhesion, good wear resistance and a wide temperature operating range. A universal grease for use on everything from stern glands to winches”

Generic white waterproof greases are also available.

Cutless Bearing

Diesel School: Is it Cutlass or Cutless?

Keeping the shaft absolutely true, supporting the thrust back towards the engine all while minimising friction is a real challenge. The fact that the entire system must be submerged in salt water means that traditional methods such as steel bearings and petroleum grease simply are simply out of the question.

The agreed solution is known as a cutless bearing in which seawater acts as the primary lubricant for your boat’s propeller shaft. The shaft is supported by a fluted rubber tube – the cutless bearing. The flutes allow sea-water to wet the prop shaft all the way to the packing material.

Problems can occur when the bearing lining and grooves wear down. This will reduce the flow of sea water and introduces looseness or play in the bearing and heating up may cause acceleration of wear.

To determine if your cutless bearing needs replacing, look for signs of wear or deterioration at both ends of the bearing (if you can see both ends). Unusual or lopsided wear patterns are indications of significant shaft misalignment issues and should be addressed immediately.

P-brackets

Every yacht has a unique combination of its underwater profile, exit angle of prop shaft and size of propeller. The distance between the stern gland and the propeller in many marine diesel installations requires that the prop shaft is supported on the outside of the hull by a P-bracket. P-brackets typically have a cutless bearing in them.